Andr

搜索"Andr" ,找到 部影视作品

导演:

主演:

剧情:

Set in the world of bugs where spiders are the cops, a detective boards a seaplane to San Francisc

导演:

主演:

剧情:

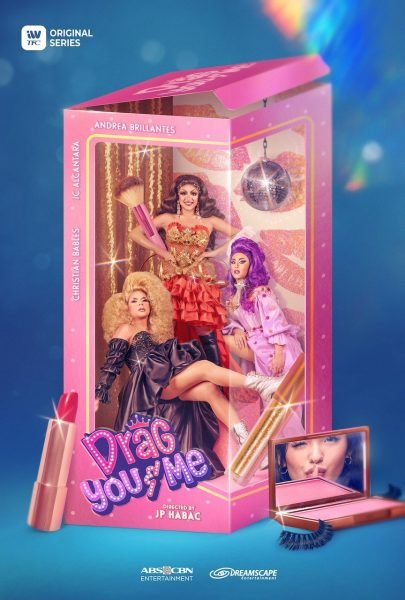

一位顺性别女性加入了国内最负盛名的变装比赛,因为她想拯救她的家和变装喜剧酒吧不被收回。然而,当她爱上竞争对手时,情况开始变得复杂……

导演:

主演:

剧情:

一群曾经的女高学生,十年后再次相聚在校园。谁知大浪袭来,世界瞬间变为末日汪洋。这群昔日同窗被困在校园之巅仅存的立足之地,尝试求生的同时纠缠在彼此的十年旧账中。

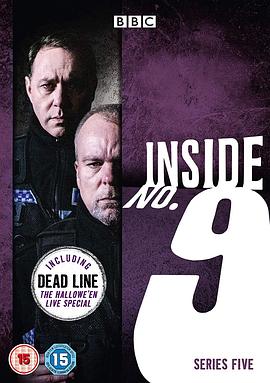

主演:

剧情:

《9号秘事》是一部英式黑色幽默悬疑喜剧。一部只有短短的几集,每一集都讲一个独立的故事。每一集只有短短的半个小时,却以十分紧凑的剧情和片尾的意外结局让观众大为赞赏。

导演:

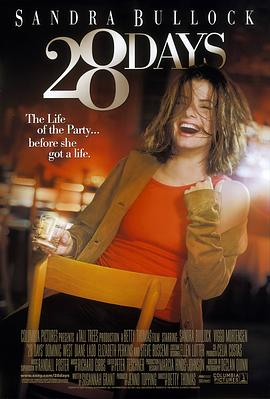

剧情:

Gwen Cummings is a successful New York writer living life in the fast lane and everyone's favo

导演:

主演:

剧情:

一个男孩被绑架,他的爸爸麦克尔·斯台格警官陷入绝望之中。他没有钱,他妻子刚刚离他而去,他作警察的工作也前途暗淡。更让他不安的是,他没有接到绑匪的信或电话。为什么?因为绑匪搞错了。他本想绑架斯台格的

导演:

主演:

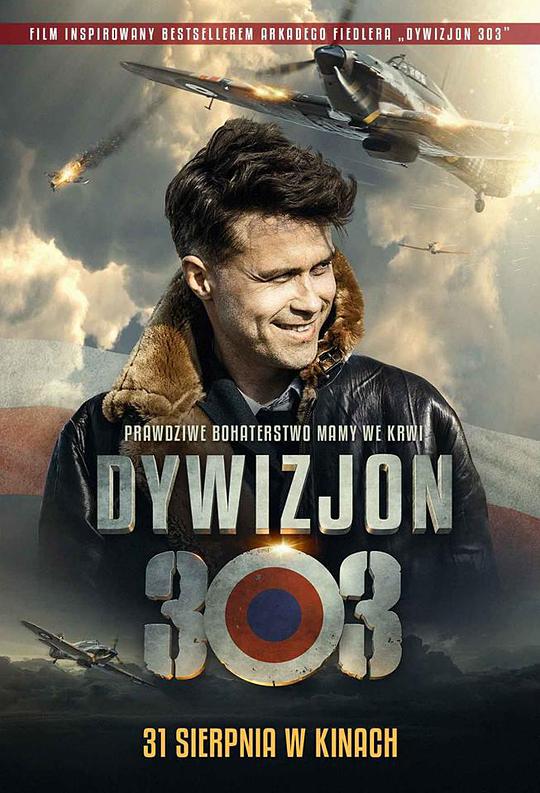

剧情:

影片讲述了二战中备受瞩目的战斗机中队的故事。中队的大多数士兵来自波兰,他们参加了不列颠之战,与英国皇家空军并肩作战,奋勇对抗纳粹的袭击。战斗中303中队击落的敌机数量达到了其他中队的三倍之多。

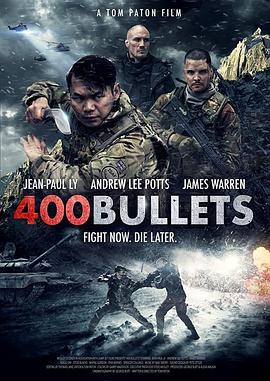

导演:

剧情:

400 BULLETS is an edge-of-your-seat Military Action story about what it means to fight for honor i

导演:

剧情:

Sakthi is a petty thief in a Chennai slum, who learns the Adimurai, the ancient and oldest form of

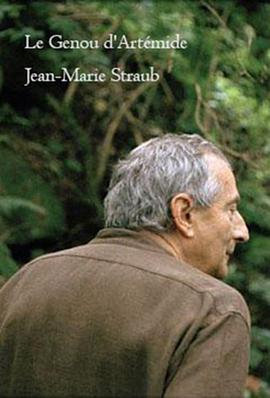

导演:

主演:

剧情:

For Le Genou d'Artemide Jean-Marie Straub once again chose a dialogue by Cesare Pavese. And no